- Home

- Michael Duffy

Drive By Page 2

Drive By Read online

Page 2

On the day after the murder Bec had been loaned to Strike Force Beldin to provide local knowledge. Having worked on a previous investigation led by Knight, when he’d asked for her again she’d assumed there was some sort of respect there. It had all gone wrong, because she couldn’t keep her mouth shut. Look and learn, her boss had said when he agreed to the secondment. Just watch and learn. But it was something she couldn’t do.

This morning she’d waited for Knight when she got to the old courts. She saw him coming up King Street with the Crown prosecutor, a tall woman with blonde hair, the solicitor in their wake. Her boss had told her the Crown’s name was Karen Mabey. Knight was going bald up top. He’d lost the moustache he’d previously sported, which made him look a lot less like a walrus. As the three reached the camera crews, Mabey stepped out and pushed her way through, face set. She had an air of authority, kind of aristocratic. Bec slipped through the big front door before them, waited in the semi-gloom to catch Knight’s attention, but the trio swept past as though she wasn’t there. Like she was some peon, a word discovered only last week in the cryptic crossword. She’d wondered if she’d ever get to use it, and now here she was, peonic herself, good view as they walked of the back of Mabey’s neck, encircled by pearls.

In the courtroom she paused for a moment, confused by the layout. It was her first time in the renovated Victorian building, and she’d rarely been in such a big room, elegant simplicity up top but at ground level a wooden maze of stairs and barriers. Like a crossword built of wood. Without looking at her, Knight pointed one way with a flabby hand, himself went the other, down to the bar table.

The public gallery was spread over three sections separated by carpeted corridors. The middle section was raised slightly and boxed by a wall. There were low walls everywhere—the people who’d built this place had a very firm idea of everyone’s place. She entered and walked down some stairs and took a seat in front, looming behind the lawyers’ pit, beyond which rose a tiered cliff of more wooden barriers, the empty judge’s seat on top beneath a canopy bearing the state’s coat of arms. She watched as Mabey introduced Knight to the defence barrister, Andrew Ferguson. Bec had seen him once in a drugs trial.

Knight went into a huddle with Mabey. It was what people did in courts, got close to each other, mouths next to ears, in their black suits or robes. Bec wondered if she should buy a dark suit herself. She had three outfits, grey, brown and dark blue. The blue one she was wearing today was getting shiny at the elbows. She was hoping the shine would go away if she got it dry-cleaned, but she wasn’t sure. It was cheap and several years old.

Two female journalists came in and took their seats at the side of the room, talking loudly. The one in the pale pink jacket was pretty. Habib was in the dock, thin and handsome in a sharp grey suit, early twenties. He was leaning over and talking urgently to his solicitor, another huddle. High cheekbones, long nose, looked too young and handsome to be a killer.

Bec glanced at the old clock behind her: five to ten. A sheriff’s officer came over, a big old guy in a blue uniform, walked with a roll. He’d made Bec for a cop, said hello, call me Jim. Ex-job, bored.

‘Optimistic?’

‘Fifty-fifty,’ Bec said, looking back at Habib. ‘That’s a nice suit.’

‘Hugo Boss, what you reckon?’ As they watched, Habib glanced away from his solicitor, another Leb, noticed Bec and adopted that acerbic expression they must practise at home, suggesting everyone is wasting their time.

Jim sniffed. ‘More than we could afford.’ Still on the suit. ‘He got legal aid?’

‘Not with Ferguson.’

One of Sydney’s best criminal barristers, and richest: people had given their homes to be defended by him. There was a queue.

‘Good job?’

‘Uni student.’

‘Father?’

‘Invalid pension.’

Ferguson charged eight thousand a day, and this trial was expected to last a month.

‘I don’t know where they get the money.’

Bec said, ‘You’re not suggesting Andrew Ferguson lives off the proceeds of crime?’

‘Don’t we all?’

She hadn’t thought of it like that.

She did know that sometimes, looking at a citizen in the dock, she was relieved it wasn’t her. But that was a different thing entirely.

Roselands Police Station, morning after Teller’s shooting

The way Homicide worked, the team would consist of a couple of detectives from the central squad and a dozen or more from local stations. Bec was keen for the experience, wanted one day to move into major crime, investigations bigger and more interesting. To play A grade.

She’d joined the navy after school, had achieved promotion and for a while it looked like a life. Then another of the few women onboard had been photographed secretly in the shower, the pictures put on the internet. There’d been an investigation and Bec had given evidence, despite being urged not to by various persons of the male persuasion. To whom she’d said, Get fucked. The photographer had been fined, not a lot, demoted one rank, moved to another ship. Bec had been disgusted and isolated, people turning on her. Inspired by one of the investigators she’d met during the case, she quit and joined the police. It was another family, although she tried not to think like that. For most of the time she succeeded.

She’d done well enough in the job, been a general detective two years now and was looking for a step up. Needed a mentor, so Knight’s request for her again had been welcome. When she arrived at Roselands he introduced his team from Homicide, Meaghan Burchell and Chris Wallace. Burchell was tall, dark-haired, long chin, Wallace thin, heavily tanned for April, looked her up and down.

‘Call me Rooster,’ he said, smiling, as they shook hands.

It was not a happy room: Knight was raging, he’d just learned no one had secured Teller’s flat. Burchell raced around making phone calls, left abruptly.

Bec said to Wallace, ‘How come—’

‘Knight wasn’t the OIC until this morning. They had Bill Gillies on it.’

‘He was inapt?’

‘Huh?’

She could have trouble with words.

‘He stuffed up?’

‘Roselands told him they had it under control. He believed them.’

There was a briefing, with lots of locals including the Roselands boss. They were addressed by Brian Harris, inspector in the Drug Squad. He was shorter than most male cops but muscly, pale skin and freckles, short ginger hair. Bec had heard of him, a shootout with bikies, armed raids on nightclubs, other stories she’d forgotten. That was the thing about major crime, you got to be in the same room as people of this quality. She was loving it.

Harris spoke now with great energy, his gaze darting as he told them about Jason Teller. Had managed a nightclub called Java in Kings Cross as a front for Sam Deeb, the big club owner and celebrity who should have been locked up years ago. Sam liked to keep his employees in defined roles, meant Teller had nothing to do with actually selling drugs. His job was security, making sure Sam’s runners got in and the competition was kept out. Making sure undercover cops were identified, police parties with sniffer dogs delayed. For this he’d been paid a grand a night for the two nights Java opened each week. Did a bit of other work, mainly as a bouncer.

‘Teller liked the ’roids,’ Harris said. ‘Looked like someone had stuck a pump in his arse and inflated him. Came here from Melbourne two years ago, total of eight years inside down there, supply and aggravated assault. Up here, bit of standover stuff, bit of drug dealing through the gym he went to, City East. Protection. A serious crim—’

‘But no longer young,’ Knight interrupted.

The big man was looking bored with Harris, or maybe irritated; there was something there, between them.

‘He was forty and not a member of any family or syndicate, so yeah, he might have been thinking about the future, taking risks to build up a nest egg. Our intel is lately he’d steppe

d up, getting coke through the airport, selling it to The Five.’ A Vietnamese gang at Fairfield, not too far away. But not too close, either.

‘That gets him to Roselands?’ said Paul Easterley, a local detective.

‘We do not know. The GPS in his car was working, so he wasn’t lost. Dangerous to get out of his car here for any reason, I would have thought.’

There was hard laughter in the room. The war between the Deebs and the local gang, the Habibs, had been running for five years, producing at least eight bodies and dozens of hospital admissions. The argument was over geography, control of drug runs in suburbs that lay between the families’ strongholds. Police efforts to stop the war had been largely futile, the combatants violent and bold; two years ago Habib associates had actually shot up Roselands Police Station. Eighteen bullets, seven going through the windows at the front, one missing a uniformed constable by forty centimetres. No one had been charged, a matter of some shame.

Harris said, ‘Teller used to meet The Five out back of a kebab shop in Wiley Park, we were waiting for the right time to bust them. Why he was here, I can’t explain it to you. Yet.’

‘No reason for The Five to knock him?’ said Knight.

‘I can’t see it. He had good product, good contacts at the airport. They needed him.’

‘Probably just a Leb thing,’ someone said. ‘They’re animals, don’t need a reason to shoot you.’

Bec looked over at the superintendent. Some commanders would stomp on such sentiments as a matter of course. But as murmurs of agreement spread around the room, he just stood with his arms folded, looking at the outsiders. Happy for them to see how things were.

A uniform said, quietly but with conviction, ‘The Lebs have turned this city into a shithole.’

‘Yeah, they’ve destroyed this place.’

‘It’s not all Lebs,’ Knight said cheerfully, and the room grew quiet. He was not being liberal, just provocative. It was his way.

‘Bullshit.’

‘Tell that to Melinda.’ Murmurs of agreement. Bec presumed she was the officer who’d almost been hit when the station was shot up.

There was conversation around the room and Knight let it go for a few seconds, until Harris and the super were looking at him irritably. He announced the meeting was over.

‘Mate, mate.’ Easterley came up to Bec; friendly man, handsome. ‘You heard the one about Ali and Mustafa?’

‘No.’

‘Ali’s walking down Haldon Street, Lakemba, and sees his buddy Mustafa driving a brand-new four-wheel drive. “Hey, bro,” he goes, “where you get the cool wheels?” And Mustafa goes, “Fatima gave it to me.” So Ali’s real surprised, he says, “I knew she liked you, bro, but a new RAV?” “Hey, bro,” goes Mustafa, “we was in Brighton and Fatima pulls off the road near the beach there. She runs down to the sand and takes off all her clothes and says, Mustafa, take whatever you want. So I took the truck!”’

There was laughter around them and Bec smiled. If you believed in tolerance when you joined the cops, the job soon beat it out of you. Easterley went on: ‘So Ali goes, “Mustafa, you’re a smart man, bro! Them clothes would never fit you anyway!”’

Boom boom.

By now there were eight on the team, two more from Homicide and others from surrounding areas. Folk of all shapes and sizes, checking each other out.

Knight said, ‘I want Rooster and Jonesy to talk to Fairfield, find out about The Five.’ He looked at Wallace. ‘We need to know more about Teller’s connection with them, whether they were happy customers, any links at all with the Habibs.’

‘Inspector Harris—’

‘Forget the druggies. Talk to the locals, okay? Boots on the ground.’

He allocated tasks, lots of tasks, then turned to Bec. ‘You manage [email protected]; I regard keeping that up to date as a sacred task.’ The investigation database. Relieved titters from the others, who’d missed out on the office job. Bec felt gutted.

Harris had been talking with the superintendent, and now brought him over to Knight, said quietly, ‘A word?’

From the glance Knight gave him, it was again clear they knew each other. There were connections between these men going back years; things Bec would never know. This sense of ignorance felt like a weight. Knight headed for the door, then stopped and looked around at the departing detectives.

‘You,’ he said to her.

Like all good cops, Bec was interested in what lawyers did, often frustrated. In an investigation you uncovered an unwieldy pile of facts, wrestled them into some sort of shape, called it a brief of evidence and handed it to the lawyers. They did their own moulding and presented something different again to the court, the prosecution case. The story’s shape might change further as the judge decided just what evidence could be presented to the jury. It was as though the legal types were producing a play that was being constantly edited. Lawyers liked to think of this as a distillation, but cops saw it as a transformation. Always it favoured the accused.

She was also interested in trials, drawn to see things from the accused’s point of view. Had no idea where this came from and it disturbed her. It was not empathy, it was more pressing, and she’d learned to keep it in the part of her where the secrets lay.

There was a mild tension in the courtroom now. She’d been to a play once, and imagined it was like this just before the curtain went up. The accused was hiding his nerves, the lawyers were trying to look relaxed, the court officials were making last-minute adjustments to their papers, computers, recording machines. All awaiting the arrival of the only missing actors, the jury and the judge.

There was a knocking from the front of the courtroom, and off to the side a door opened. Everyone stood up. An old bloke in some sort of black gown came out but this was not the judge. His Honour followed, scarlet gown, grey beard matching his wig. Glasses of course, these folk did a lot of reading. He bowed and sat down, and a woman in another black gown announced, ‘The Queen against Habib.’

Knight appeared next to Bec, murmured as their backsides descended onto the hard wooden bench, ‘G’day.’ Whiff of some ancient brand of aftershave designed not to smell too good.

The lawyers identified themselves to the judge and began to argue over whether a certain witness could be called. Bec knew the jury panel was waiting outside and would not be brought in until the barristers and the judge had established certain parameters. Such a conversation was known as a voir dire and it could be hard for a layperson to follow. She turned to see who else was here, but it was the same as before, the cute reporter in the pink jacket now peering at her phone. Still no one from Teller’s side. Bec recalled his funeral: big men with thick necks, dark suits and sunglasses, a few young women, all blonde, most in big hats as though ready for a day at the races. For them black meant cocktail rather than funeral, short skirts and lots of cleavage. None of them had looked like family.

Usually the victim’s mother would attend a trial, at least. She considered this. Her falling-out with Knight during the investigation had been because of her doubts about Teller’s identity. The sergeant had rejected the idea with scorn, and she’d been unable to produce any firm evidence. A defining moment in her career—as in poor definition. Knight had grown impatient with her hazy suspicions, kicked her out.

And yet: there was no mother here today.

Might be dead, though. Teller had been middle-aged, from a social background unknown for healthy living. Like Bec’s own.

She wondered why she’d been given so little warning of the trial. Maybe Knight was just disorganised. Last night Walton had told her that he’d been out of town recently, on a job in South Australia. Bec called a friend from Adelaide who worked in the navy’s equivalent of the military police, the one who’d inspired her to become a cop after the business on the Merimbula six years ago. He rang back an hour later to say Knight had been brought down to investigate possible corrupt behaviour at a local police station, drugs and a brothel involved.

&nbs

p; ‘Senior cop was a client, not dodgy himself, but it was delicate.

Knight sorted it all out, couple of pleas.’

No trial and most of the details never made public. ‘He did well?’

‘Everyone down there is very happy.’

Mate, it was a sad day is all I can say for the family, when I heard this lie. Rafiq was always the golden boy, the baby we all looked after, the first Habib to go to uni. So to hear the jacks was targeting him over this Jason Teller thing, it made a lot of people angry.

The first I heard was when the papa rung me at work. I wasn’t working that moment, it was lunch and me and the guys were arguing over the Toyota symbol, one of the things we do before the league gets going or if there’s nothing on the telly. Bones reckons the symbol is a cowboy—you know, it’s a loop standing on its end with a curved line halfway up, like the brim of a hat? But like Ali and some of the other guys say, why would the Japs use a cowboy when they hated the Yanks and wanted to drive their cars out of the market?

I pulled the phone out of my trousers when it rang and was glad it was lunchtime because my boss, Chris Taylor, has basically given me a warning, like, no more family business in work time. I told this to the papa one day, said he should send me texts. But the papa is not so good with the technology. Farid was fierce, he told me to keep the phone on anyway, he said if I get into any strife to let him know and he’d go and see Chris Taylor. As this would be the greatest disaster of the century I am right keen to avoid it, but I still need to take the calls. It is this tricky situation I am in that is very hard to explain to people who do not have strong family bonds.

Mr White had rung our father and although the papa can speak English a bit he’s not that good because he was born in Lebanon and never even heard anyone speak English until he came here when he was twenty-two. The mama is just the same so they have always needed us kids to translate for them. First it was Imad, then Farid, and now it is me.

Mr White has been our solicitor since my parents bought their house back in the nineties and he’s handled all the difficulties we brothers have had, Imad mainly because Farid has managed to keep out of trouble generally. Some people say Farid is smarter than Imad, but Imad is a genius so I don’t think that is possible. My personal opinion is that Imad just made all the mistakes because he is the oldest, and Farid learned from them.

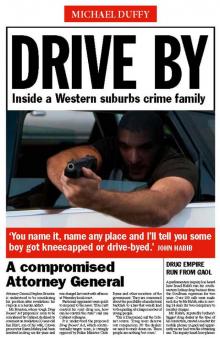

Drive By

Drive By The Tower

The Tower The Simple Death

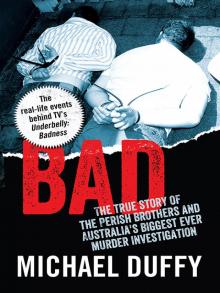

The Simple Death Bad

Bad Sydney Noir

Sydney Noir Call Me Cruel

Call Me Cruel